Voskhod 2

| Voskhod 2 Восход-2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mission insignia |

|||||

| Mission statistics | |||||

| Mission name | Voskhod 2 Восход-2 |

||||

| Spacecraft type | Voskhod 3KD | ||||

| Spacecraft mass | 5,682 kg (12,530 lb) | ||||

| Crew size | 2 | ||||

| Call sign | Алмаз (Almaz - "Diamond") | ||||

| Booster | Voskhod | ||||

| Launch pad | Gagarin's Start, Baikonur Cosmodrome[1] | ||||

| Launch date | March 18, 1965 07:00 UTC | ||||

| Spacewalk begin | March 18, 1965 08:34:51 UTC over north central Africa |

||||

| Spacewalk end | March 18, 1965 08:47:00 UTC over eastern Siberia |

||||

| Landing | March 19, 1965 09:02:17 UTC | ||||

| Mission duration | 1d 2h 2m 17s | ||||

| Number of orbits | 17 | ||||

| Apogee | 475 km (295 mi) | ||||

| Perigee | 167 km (104 mi) | ||||

| Orbital period | 90.9 min | ||||

| Orbital inclination | 64.8° | ||||

| Crew photo | |||||

|

|||||

| Voskhod 2 crew | |||||

| Related missions | |||||

|

|||||

Voskhod 2 (Russian: Восход-2) was a Soviet manned space mission in March 1965. Vostok-based Voskhod 3KD spacecraft with two crew members on board, Pavel Belyaev and Alexei Leonov, was equipped with an inflatable airlock. It established another milestone in space exploration when Alexei Leonov became the first person to leave the spacecraft in a specialized spacesuit to conduct a 12 minute "spacewalk".

Contents |

Crew

| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Pavel Belyayev First spaceflight |

|

| Pilot | Alexei Leonov First spaceflight |

|

Backup crew

| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Dmitri Zaikin | |

| Pilot | Yevgeni Khrunov | |

Reserve crew

| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Viktor Gorbatko | |

| Pilot | Pyotr Kolodin | |

Mission parameters

- Mass: 5,682 kg (12,530 lb)

- Apogee: 475 km (295 mi)

- Perigee: 167 km (104 mi)

- Inclination: 64.8°

- Period: 90.9 min

Space walk

- Leonov - EVA 1 - March 18, 1965

- 08:28:13 UTC: The Voskhod 2 airlock is depressurized by Leonov.

- 08:32:54 UTC: Leonov opens the Voskhod 2 airlock hatch.

- 08:34:51 UTC: EVA 1 start - Leonov leaves airlock.

- 08:47:00 UTC: EVA 1 end - Leonov reenters airlock.

- 08:48:40 UTC: Hatch on the airlock is closed and secured by Leonov.

- 08:51:54 UTC: Leonov begins to repressurize the airlock.

- Duration: 12 minutes

Mission highlights

The Voskhod 3KD spacecraft had an inflatable airlock extended in orbit. Cosmonaut Alexey Leonov donned a space suit and left the spacecraft while the other cosmonaut of the two-man crew, Pavel Belyayev, remained inside. Leonov began his spacewalk 90 minutes into the mission at the end of the first orbit. Cosmonaut Leonov's spacewalk lasted 12 minutes and 9 seconds (08:34:51–08:47:00hrs UTC), beginning over north-central Africa (northern Sudan/southern Egypt), and ending over eastern Siberia.

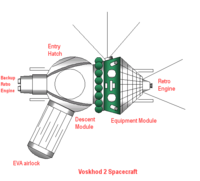

The Voskhod 2 spacecraft is a Vostok spacecraft with a backup, solid fuel retrorocket, attached atop the descent module. The ejection seat was removed and two seats were added, (at a 90-degree angle relative to the Vostok crew seats position). An inflatable exterior airlock was also added to the descent module opposite the entry hatch. After use, the airlock was jettisoned. There was no provision for crew escape in the event of a launch or landing emergency. A solid fuel braking rocket was also added to the parachute lines to provide for a softer landing at touchdown. This was necessary because, unlike the Vostok, the crew lands with the Voskhod descent module.

Though Leonov was able to complete his spectacular spacewalk successfully, both that feat and the overall mission were plagued with problems. After his 12 minutes and 9 seconds outside the Voskhod, Leonov found that his suit had stiffened to the point where he could not re-enter the airlock. Leonov worked around this by allowing some of his suit's pressure to bleed off, making it easier for him to bend the joints.

The two crewmembers subsequently experienced difficulty in sealing the hatch properly, followed by a troublesome re-entry in which malfunction of the automatic landing system forced the use of its manual backup. The manual re-entry culminated in a landing well outside of the flight's intended landing zone in an inhospitable and heavily-wooded part of the Ural Mountains, forcing the two cosmonauts to spend a night surrounded by wolves before they could be rescued by their recovery team.

General Kamanin's diary later gave the landing location of the Voskhod 2, Saransk (ball), as: "54 deg 12 min North, 45 deg 10 min East." Also according to General Kamanin's diary, a commander of one of the search helicopters reported finding Voskhod 2, "On the forest road between the villages of Sorokovaya and Shchuchino, about 30 kilometers southwest of the town of Berezniki, I see the red parachute and the two cosmonauts. there is deep snow all around ..."

The capsule is currently on display at the museum of RKK Energiya in Korolyov, near Moscow.

Voskhod 2 EVA details

On reaching orbit in Voskhod 2, Leonov and Belyayev attached the EVA backpack to Leonov’s Berkut (“Golden Eagle”) space suit, a modified Vostok Sokol-1 intravehicular (IV) suit. The white metal EVA backpack provided 45 minutes of oxygen for breathing and cooling. Oxygen vented through a relief valve into space, carrying away heat, moisture, and exhaled carbon dioxide. The space suit pressure could be set at either 40.6 kPa (5.89 psi) or 27.40 kPa (3.974 psi).[2]

Belyayev then deployed and pressurized the Volga inflatable airlock. The airlock was necessary because Vostok and Voskhod avionics were cooled with cabin air and would overheat if the capsule was depressurized for the EVA. The Volga airlock was designed, built, and tested in nine months in mid-1964. At launch, Volga fitted over Voskhod 2’s hatch, extending 74 cm (29 in) beyond the spacecraft's hull. The airlock comprised a 1.2 m (3.9 ft) wide metal ring fitted over Voskhod 2’s inward-opening hatch, a double-walled fabric airlock tube with a deployed length of 2.50 m (8.2 ft), and a 1.2 m (3.9 ft) wide metal upper ring around the 65 cm (26 in) wide inward-opening airlock hatch. Volga’s deployed internal volume was 2.50 m3 (88 cu ft).

The fabric airlock tube was made rigid by about 40 airbooms, clustered as three, independent groups. Two groups sufficed for deployment. The airbooms needed seven minutes to fully inflate. Four spherical tanks held sufficient oxygen to inflate the airbooms and pressurize the airlock. Two lights lighted the airlock interior, and three 16mm cameras — two in the airlock, one outside on a boom mounted to the upper ring — recorded the historic first spacewalk.

Belyayev controlled the airlock from inside Voskhod 2, but a set of backup controls for Leonov was suspended on bungee cords inside the airlock. Leonov entered Volga, then Belyayev sealed Voskhod 2 behind him and depressurized the airlock. Leonov opened Volga’s outer hatch and pushed out to the end of his 5.35 m (17.6 ft) umbilicus. He later said the umbilicus gave him tight control of his movements — an observation purportedly belied by subsequent American spacewalk experience. Leonov reported looking down and seeing from the Straits of Gibraltar to the Caspian Sea.

After Leonov returned to his couch, Belyayev fired pyrotechnic bolts to discard the Volga. Sergei Korolev, Chief Designer at OKB-1 Design Bureau (now RKK Energia), stated after the EVA that Leonov could have remained outside for much longer than he did, while Mstislav Keldysh, “chief theoretician” of the Soviet space program and President of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, said that the EVA showed that future cosmonauts would find work in space easy.

The government news agency, TASS, reported that, “outside the ship and after returning, Leonov feels well”; however, post-Cold War Russian documents reveal a different story — that Leonov’s Berkut space suit ballooned, making bending difficult. Because of this, Leonov was unable to reach the shutter switch on his thigh for his chest-mounted camera. He could not take pictures of Voskhod 2, nor was he able to recover the camera mounted on Volga which recorded his EVA for posterity. After 12 minutes Leonov re-entered Volga.

Recent accounts report Cosmonaut Leonov violated procedure by entering the airlock head-first, then became stuck sideways when he turned to close the outer hatch, forcing him to flirt with decompression sickness (the “bends”) by lowering the suit pressure so he could bend to free himself. Recently, Leonov said that he had a suicide pill to swallow had he been unable to re-enter the Voskhod 2, and Belyayev been forced to abandon him in orbit.[2]

Doctors reported that Leonov nearly suffered heatstroke — his core body temperature increased by 1.8°C (3.2°F) in 20 minutes; Leonov said he was up to his knees in sweat, which sloshed in the suit. In an interview published in the Soviet Military Review in 1980, Leonov downplayed his difficulties, saying that “building manned orbital stations and exploring the Universe are inseparably linked with man’s activity in open space. There is no end of work in this field.”

See also

- Extra-vehicular activity

- List of spacewalks

References

- ↑ "Baikonur LC1". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/sites/baiurlc1.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Portree, David S. F.; Robert C. Treviño (October 1997). "Walking to Olympus: An EVA Chronology" (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History Series #7. NASA History Office. pp. 15–16. http://history.nasa.gov/monograph7.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

External links

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||